Wellness is everywhere – but the industry can be guilty of harnessing our fears around chronic illness and disability to sell us products

I once made my own celery juice every day for five weeks because someone online said it would improve my chronic fatigue. I stopped when I realised the self-declared expert got his ‘medical insight’ from ghosts.

As a disabled, chronically ill woman, I have invested in my fair share of failed wellness products. I am, unsurprisingly, still sick, with organs stuck together by endometriosis, and often find myself wedded to my bed with fatigue. Despite this, I’m still susceptible to the wellness trends that take over my social media pages every week. Some might say there is no harm in buying into something that has a slim chance of making you feel better, but the way that the wellness industry presents products as cures to the incurable does more harm than good to the lives of people who are already struggling to stay well.

In 2022, the wellness industry was estimated to be worth $4.4 trillion, and that figure is predicted to keep growing. For a healthy person (that is someone living without a long-term chronic condition impacting their day-to-day life), the desire to maximise their health is often in aid of optimising their time. Time is a commodity in the capitalist society we live in, and in order to get the most out of life, we are told to maximise our time by improving our productivity. Over the Christmas break, I was inundated with messages from friends who were struck by viruses: stomach bugs, influenza, COVID. The most common complaint? I don’t have time to be sick. That phrase felt particularly hard to hear, because it is only uttered by people who do not live with permanent sickness.

“People are responding to decades of public health and political messaging that our health is our own responsibility and that, to be good citizens, we need to take care of our own health through individual actions rather than through collective resources that benefit everyone (eg social support, public health, accessible urban infrastructure, etc),” says Colleen Derkatch, associate professor at Toronto Metropolitan University and author of Why Wellness Sells. “They’re also responding to contemporary capitalist values of maximising investments and efficiency, which figure the body as both a project and a resource for productivity.”

As wellness trends pervade our everyday lives, individuals are sucked into using products that they think are helping them improve, as Derkatch describes, their body’s ability to be productive. Those same individuals want to pass on this knowledge to others in their lives, including those who are chronically ill. “A friend invited me round for what I thought was a dinner… but in fact was a pitch for the supposed curative powers of nutritional and superfood powders,” says Dr Rachel Marsden, a chronically ill woman and part of the research team at the Stomach Ache Project, which seeks to understand the experiences of people living with undiagnosed gastrointestinal issues. “I was blindsided and cornered on arrival, stayed as long as my anxiety and frustration would take, before I made my excuses to leave.”

The idea that complex health needs related to the degeneration of someone’s gastrointestinal system could be cured with spirulina powder exemplifies one of the key seductions of the wellness realm: that you are being granted inside knowledge that hacks the system; a shortcut or fast track to feeling better. “A big selling point of wellness is that it’s a kind of secret that resists mainstream culture,” says Derkatch. “I’ve seen countless Instagram influencers peddling supplements by saying things like ‘doctors won’t tell you this but…’”

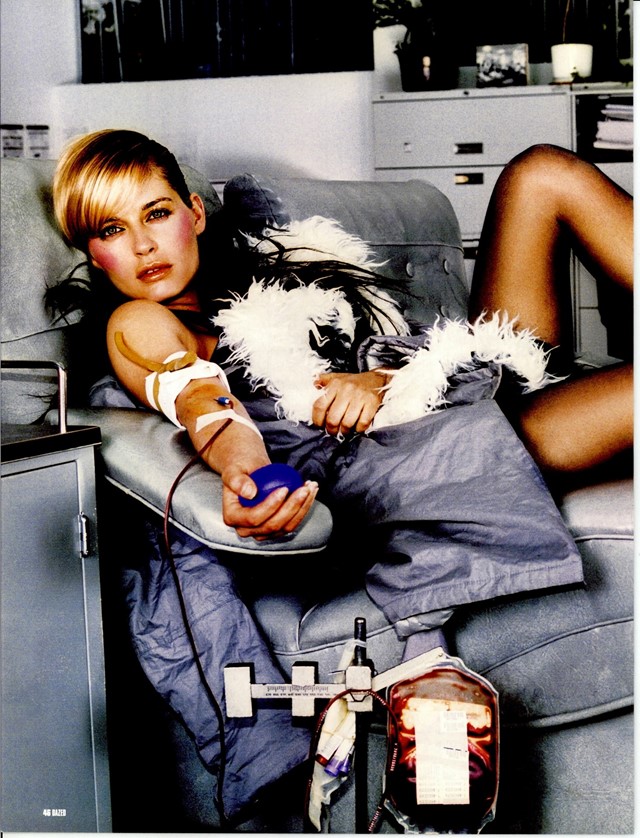

That people believe they have to find alternative ways to treat their illnesses and ailments points to a loss of confidence in medical healthcare. Most chronic conditions, like ME and Endometriosis, are gravely underfunded and under-researched – in some cases, patients who have them are made to believe it is all in their heads. So many people are being failed by the traditional medical pathways available to them that seeking out alternative options is a way of holding onto hope. I myself have spent hundreds of pounds on products, courses and machines in hope of finding pain-free moments, despite knowing all the myths that products like greens powders or IV Vitamin C perpetuate.

Alongside the desire to keep up with the fast pace of capitalism and its culture of hyper-productivity, there is a secondary reason for the pursuit of optimal health: the conflation of sickness and moral failing. From historic religious texts to contemporary medical systems that tell people who live in chronic pain they can simply think their way out of it, society often blames chronically ill people for their illnesses. “People view my pain as a result of my anxious thinking, something I can eradicate by setting a spiritual goal or consuming five cups of herbal tea a day,” says Kai, 27, who lives with fibromyalgia. From being given essential oils for muscle pain to being told to drink thyme tea for their ‘ailments’, they are constantly having wellness products pushed onto them by friends and even strangers in passing.

“The whole generating idea behind wellness is that we are both not as well as we once were and not as well as we could be, and a key part of that is that disability and sickness are failures of the body and the person,” says Derkatch. “In this view, people become responsible for ensuring their bodies and minds are functioning optimally to ensure they do not become sick or disabled.” Disability has been long established as a euphemism for less than: those who are too unwell to work do not contribute to society, and therefore deserve less – or so the logic of neoliberal capitalism would hold. Thus, non-disabled people continuously seek to maintain or improve their health, in fear of being seen this way.

Amelia is a yoga teacher living with endometriosis. She explains to Dazed that some of the most ableist and troubling interactions she received for her condition were from others within her industry, which prides itself on wellness and the pursuit of health. “I was asked if I had tried certain breathing practices or techniques that a particular teacher taught. I was advised to see yoga teachers that specialised in ‘well woman’. The attitude of these teachers was all about getting in tune with the cycle as a cure-all for menstrual issues. That was insulting.”

Amelia trains yoga students now and is sure to inform them that it was surgery and prescription medication that helped her disease, not these classes. “I’m quite emphatic that yoga did not help me and that the yoga industry made me feel like I wasn’t doing enough to help myself – like victim blaming. It made me think I could heal myself so it took longer for me to get proper medical help.” Amelia’s experience is an example of how wellness products and trends can further harm chronically ill people. Failing to seek out medical care because you are being told you can fix it at home can have disastrous impacts on diseases like endometriosis, which when left untreated can adhere a person’s organs together, and cause irreversible damage.

So is the wellness industry inherently ableist? The answer is more complicated than yes or no. Of course healthy people don’t consciously pursue wellness to harm chronically ill people, but the wellness industry is guilty of using scaremongering as well as misinformation and false claims, to convince people that the cure to their problems – whether that is burnout from capitalism or an incurable disease – is a product they can sell you.

Join Dazed Club and be part of our world! You get exclusive access to events, parties, festivals and our editors, as well as a free subscription to Dazed for a year. Join for £5/month today.