Medical conditions affecting people with vulvas are notoriously understudied, but new developments in the field suggests this might be changing

Smear tests. Thrush. IUD insertions. Painful sex. Excruciating UTIs. Hardly a week goes by without a friend uttering some complaint about their vulva* – an itch, an ache, an invasive medical procedure.

A third of people with vulvas experience severe reproduction health problems in a given year. However, despite the pervasiveness of gynaecological discomfort the area remains chronically under-researched and misunderstood. There are over five times more studies into erectile dysfunction than there are into premenstrual syndrome (PMS), despite the fact that over 90 per cent of women suffer from PMS – with symptoms that can include anxiety, depression and debilitating pain – compared to 19 per cent of men who struggle to get it up. It’s no surprise that discrepancies like these are even more pronounced in the healthcare of trans people and women of colour.

In 2018, science journalist Rachel E. Gross came face to face with these systemic failings. She’d been going back and forth to the doctors for a month, but it took multiple rounds of antibiotics and antifungals for her gynaecologist to finally diagnose her with bacterial vaginosis (BV) – the most common vaginal condition between the ages of 15-44. By this point, the symptoms had become unbearable. It was disrupting her sleep; wrecking her self-esteem.

There was one last option, her gynaecologist told her. It was “essentially rat poison”. “I was just really shocked,” she recalls, “that a gynaecologist who had gone through med school and spent years and years treating women didn't have something better to offer me”. Gross has since written a whole book about vulvas, and the cultural myths that have enshrouded them throughout history (her Instagram handle – @gross_out – reflects at least one).

The original Latin term for the vulva, used until 2019, was pudendum which directly translates as the part to be ashamed of. In Ancient Greece, physicians blamed female suffering on their “wandering wombs”, a consequence of them not bearing children soon enough. Ovaries were regarded as female testicles until the 17th century, when they got their current name, deriving from the Latin ovarius, literally: “egg-keeper”.

This knowledge gap has left behind a legacy of male-centric healthcare, and a measly understanding of how different treatments affect women and girls. Between 1997 and 2000, the US Food and Drug Administration took 10 drugs off the market due to severe side effects. Eight caused greater health risks in women. “We literally know less about every aspect of female biology compared to male biology,” Dr Janine Austin Clayton, an associate director for women’s health research at the United States National Institutes of Health told The New York Times.

But recent developments suggest that things might finally be changing. Last month, scientists at Harvard developed the world’s first ‘vagina-on-a-chip’ – a small device containing live human cells that replicates the cellular environment of the vaginal canal. What’s so promising about this technology is that it offers a controlled environment that’s outside the human body. Scientists can test and retest how different bacteria (and eventually new treatments) affect the vagina, without needing a willing patient to subject themselves to these experiments.

“This is just the start”, Aakanksha Gulati, co-author of the study, told Dazed. “We just started to understand one disease called bacterial vaginosis, but we could do so much more with these chips.”

In 2022 alone, scientists developed a number of potentially life-changing treatments for conditions that predominantly affect women and people with vaginas. One British lab developed the first antibiotic in 20 years to treat UTIs, while researchers in North Carolina found that a dissolving vaccine could be equally effective.

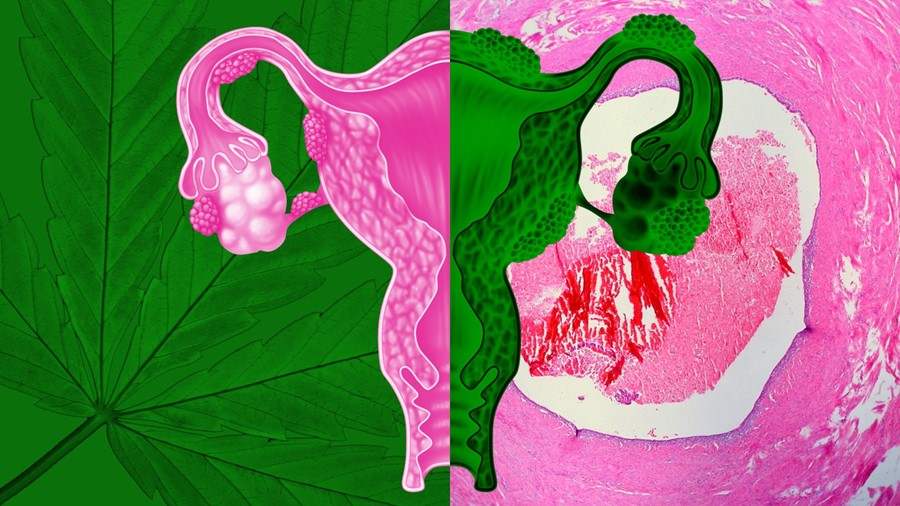

In the field of endometriosis, a Texas lab discovered that oleuropein – a natural compound found in olive leaves – could be safer and cheaper than current treatment options. Meanwhile, scientists in California studied nearly 400,000 cells and created the first single-cell RNA-sequencing comparison of endometrial tissues – essentially a roadmap for researchers around the world to more effectively diagnose the disease. “It’s jumped us forward a whole new chapter in our book in learning about endometriosis,” Kate Lawrenson, an associate professor in the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology at Cedars-Sinai, and co-author of the study told Dazed.

Endometriosis affects as many as 1 in 10 women and those assigned female at birth in the UK, yet it takes an average of 7.5 years for it to be diagnosed. While symptoms include severe pain and excessive bleeding, patients are frequently treated as if their pain is purely psychological, with over 75 per cent misdiagnosed with a mental and/or other physical health problem before receiving the correct diagnosis.

Lawrenson believes that part of what’s slowed progress is the limited cellular data on the condition. “There are very few places where endometriosis care happens in a centralised place,” she explains. “Someone might see their primary care doctor or their gynaecologist and get different pieces of the puzzle met”. She hopes that the cellular atlas will be a game-changer for endometriosis diagnostics and treatments, as well as shedding light on other conditions that disproportionately affect women, such as immune dysregulation. But in order for research progress to ever match that into conditions that affect men, foundational change is required – “to change how society views women’s experiences of pain and what is normal and what is typical”. “That is a much more complex issue”, she emphasises.

Science writers like Gross play an important role in rewriting these narratives; overwriting a legacy of medical bias and creating new frameworks to understand our bodies. “A lot of us don’t think about our uterus or ovaries, except when it comes to menstruation or baby-making”, she says. “These body parts do more than produce babies… they’re really important to pleasure, immunity and regeneration.”

The fact that research into conditions like endometriosis and BV are receiving adequate investment makes her hopeful. It “really shows that at least some subset of the medical community is prioritising female well-being” – beyond making babies. And as we move away from the male-centric model that has dominated medical history for so long, all bodies of all genders will benefit.