Sex positivity has changed the face of the art world, as artists like Tracey Emin and Robert Mapplethorpe lose their controversial edge – perhaps it’s for the best

This article is part of our Future of Sex season – a series of features investigating the future of sex, relationships, dating, sex work and sex worker rights; tech; taboos; and the next socio-political sexual frontiers.

It’s 1865. You’ve popped along to the Paris Salon to take a look at the cutting edge of contemporary art, and you notice that a crowd has formed around a large canvas. The painting, Édouard Manet’s Olympia, shows a young woman lying nude on a bed, receiving a bunch of flowers from her servant. A disgruntled murmur ripples through the crowd, building to a chorus of shouts, jeers, and accusations of obscenity. Security guards are brought in to protect the painting, and it is moved higher on the gallery wall, out of reach of disgruntled visitors’ canes and umbrellas.

Why are the gallery goers so angry, when nudes have been a staple subject of painting, on and off, since the ice age? Well, they say that several symbols in the painting identify Olympia as a demimondaine, or a prostitute. This is not just any nude woman. It is a woman who has sex! For work! (How do the critics recognise the trademarks of a sex worker, you ask? It’s a good question – curiously, they aren’t too keen to share the answer.)

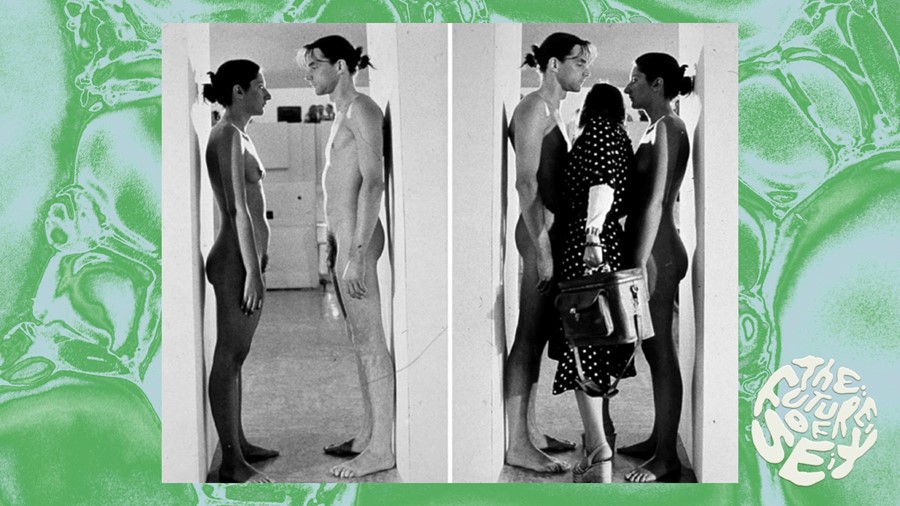

Cut to 1977. Serbian artist Marina Abramović is staging her latest performance work, Imponderabilia, at the Galleria d’Arte Moderna, Bologna. She stands in the doorway to the gallery, opposite her then-partner Ulay – both are fully naked, and to get inside visitors have to squeeze between them, through a metaphorical “birth canal”. After just 90 minutes, police descend on the gallery and shut the performance down, once more on grounds of obscenity.

Now, finally: 2004. Tracey Emin’s Everyone I Have Ever Slept With 1963-1995 – a tent appliquéd with the names of everyone she had shared a bed with (not necessarily had sex with) up to that point – is destroyed alongside dozens of other seminal YBA works in a warehouse fire. Critics are… less than sympathetic. “Didn’t millions cheer as this ‘rubbish’ went up in flames?” asks the Daily Mail. The Independent’s Tom Lubbock, meanwhile, argues that Emin’s artwork “wouldn’t be very hard” to recreate, adding in a snide aside: “It might need some updating since 1995.”

In case the recurring theme isn’t immediately obvious: sex has been causing a stir in the supposedly liberal art world for centuries. At best, this puritanical backlash has involved dismissing art as “obscene” – i.e. “offensive, rude, or disgusting according to accepted moral standards” – to undermine the artist’s best intentions. At worst, it’s involved attempts to get books, films, and artworks outright banned, from Gustave Courbet’s infamous L’Origine du monde, to an uncut version of The Human Centipede 2.

On the other hand, this has also made obscenity a powerful tool that artists and activists have leveraged through history. Rarely does a conventional masterpiece make headlines like a controversial nude, and this has allowed artists to smuggle their political beliefs and ideologies to a broader audience. Sometimes, there’s not much smuggling required – it’s pretty obvious, for example, that the porn shoot images of Cosey Fanni Tutti’s Prostitution (1976) condemn sexual double standards; similarly, in Robert Mapplethorpe’s photographs of gay S&M, the artist’s stance on the conservative sexual politics of the 1980s is quite literally black and white. (Both of these examples were subjected to much controversy and censorship in their day; today, they’re hailed for their revolutionary politics.)

That being said, our attitudes toward sex are obviously changing. According to a 2022 Gallup poll, people’s attitudes toward premarital sex are considerably more favourable than they were just 20 years ago. The same goes for sex between teenagers, and for same-sex relationships. On a related note, the subject has entered mainstream conversations via explicit TV shows like HBO’s Euphoria or the BBC’s Normal People, and in exploitative adverts that dress aubergines in BDSM gear. Plus (and this feels almost too obvious to state) the proliferation of online porn means that images of sex are, for better or worse, only a tap of the finger away at any given time of the day.

The question is: now that sex has emerged from the murky underground, has it lost some of its provocative edge – the thing that once riled up the establishment, and made it such a powerful political tool? How shocking will future Tracey Emins or Robert Mapplethorpes be to their viewers, or to the institutions they critique, if we continue to celebrate and destigmatise sex (as in most cases we should)?

An upcoming Marina Abramović retrospective, opening in September 2023 at London’s Royal Academy of Arts, might help to answer some of these questions. Notably, the show is said to include Imponderabilia, the artist’s nude performance piece that was axed by police all those years ago. Admittedly, the original performers won’t be taking part (Ulay has since passed away, and Abramović has chosen to bring in new nude models). Visitors will also be allowed to circumvent the performance by a different route, presumably in response to increased conversations about consent (or because the gallery doesn’t want to miss out on valuable ticket sales).

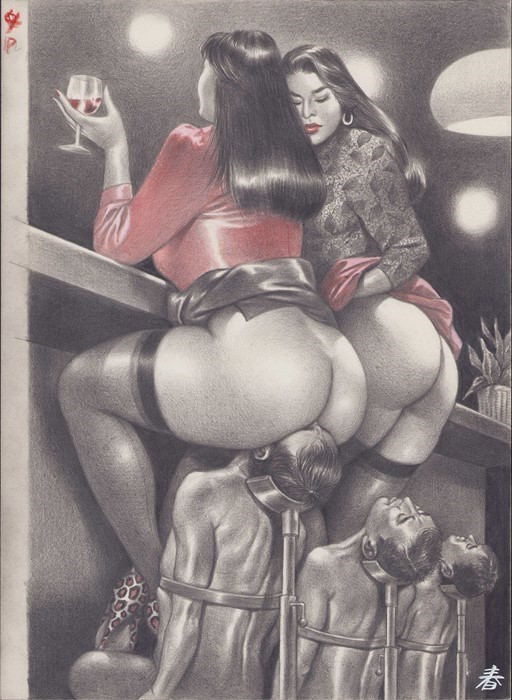

Nevertheless, it seems significant that now is considered the right time for a major gallery to resurrect a performance piece that was deemed “too obscene” to remain on show a few decades ago. It’s a decision that coincides with a proliferation of exhibitions dedicated to queer representations of sex (once also deemed too “obscene” for public consumption), or the rise of artists such as Steph Wilson or Cecily Brown, whose only-sometimes-erotic nudes attempt to transcend the male gaze. It comes a year after Jenny Saville’s record-breaking nudes were placed in conversation with Italian Renaissance masterpieces in Florence, and two years after an outpouring of art-world affection for the late fetish artist Namio Harukawa, a figure long relegated to porn magazines. Sex, on the surface, seems less controversial than ever before.

That’s not to say that your Tory uncle is about to embrace nude performance art, of course, or even stifle a sexually-repressed sneer when Tracey Emin’s condom-strewn bed pops up on the TV. (Although, lest we forget, Emin gifted her neon artwork More Passion to the Tory government back in 2011…) Similarly, it would be pointless to deny that puritanical groups will keep picketing exhibitions they don’t like, especially when artists’ representations of sex intersect with more controversial contemporary issues, such as race, religion (see: Andres Serrano’s Piss Christ), or gender identity.

Then, there’s the work of artists such as Puppies Puppies (real name Jade Guanaro Kuriki-Olivo). In June this year, the US-based artist restaged Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Rape) at Art Basel, decades after Mendieta first performed it – posing for hours in her apartment, with her underwear around her ankles and blood on her buttocks and legs – in response to the rape and murder of a student in 1973. Needless to say, this depiction of sexual assault transcends the conventional definition of controversial sex-based art; its provocation lies in the violent and non-consensual nature of the implied act. However, the performance wasn’t even the main source of controversy surrounding Puppies Puppies at Art Basel 2022.

What proved more provocative? A bronze statue that the artist had installed in the city, depicting a nude trans woman, underlined with the word “Woman”. Draped in a trans pride flag, Puppies Puppies walked to this sculpture after the Mendieta performance, to give it a full face of make-up. Others had more insidious intentions for the statue, though. While it was installed in the city, it was also spat on by passersby, and even provoked people to send DMs containing death threats and slurs to the artist via social media.

Unsurprisingly, Puppies Puppies identifies cisgender men and TERFs as the main perpetrators of this hatred – people whose sexual expression has, ironically, already benefitted from the art of years gone by. “All of these narrow-minded belief systems seem to be a big part of all the transphobic backlash I’ve received from making a bronze sculpture/self portrait of myself naked,” she tells Dazed. “Even though nude bronze sculptures exist all over Europe without any resistance or hatred, the declaration of the word ‘Woman’ on the small plinth below my feet caused quite a stir with people that are transphobic.”

This is an important distinction: as recent artworks that explicitly deal with cisgender sex are canonised in contemporary culture, the mere sight of a nude transgender body is still, it seems, enough to provoke public outbursts of fury and vitriol. Often, these outbursts echo the moral policing that was levelled at “obscene” art going back to the Impressionists, too, deeming the Woman statue “unnatural” or a “perversion”.

“I am aware of the inherent political gravity my body and being come with as a trans woman,” Puppies Puppies adds. “I also think about the stigmas and assumptions I’ve experienced that come with being a trans woman of colour.” The nude self-portrait she presented in Basel was, largely, an attempt to explore these aspects of being a woman of trans experience. “My body and brain are a part of my experience and I utilise myself as a way to try and dig deeper,” she says. “To understand why I’m treated the way I am as a trans woman.”

This statement of intent serves as a hopeful reminder that the influence of sexual mores on art doesn’t only flow in one direction. To some extent, the long line of artists whose work has been deemed “obscene” are to thank for the relative sexual liberation of the 2020s and beyond. It follows that today, the provocative work of artists like Puppies Puppies remains a vital tool to shine a spotlight on the realities of transgender sexuality – her revival of Ana Mendieta’s Untitled (Rape) brings to light the alarming rates of sexual violence against transgender people; her nude statue is a “catalyst for bringing transphobic beliefs to the surface”.

It’s undeniable that these controversial artworks are stoking conversation about a broader spectrum of sexualities and gender identities, otherwise Puppies Puppies’ DMs wouldn’t be blowing up with comments. And, while many of the comments are currently stacked against the artist, the same could once be said of Manet, or Abramović, or Mapplethorpe’s detractors – now, it’s hard to imagine the increasingly-liberated world we live in today could exist if these arguments had never taken place.

Looking to the future, it’s possible to imagine an end to “obscene art” altogether. Where depictions of consensual sex are concerned, the sooner the better. More than anything, cries of obscenity have acted as a barometer for moral acceptability, indicating where we’re at when it comes to attitudes about sex. If old Tories are walking past Tracey Emin’s sex-positive neon signs every day without batting an eye, it’s pretty safe to say that her message is well on the way to being normalised. Let’s hope that we’ll be able to say the same about trans art in the near future, as it shifts the establishment’s perspective on the autonomy and joy of bodies that don’t look like their own. Art losing its shock factor will be a small price to pay for the equal right to enjoy sex in the real world.