Exploring family trauma and the history of blackface, the major new commission is now on show in Rotterdam

Steve McQueen’s latest artwork is one of his most personal to date, and yet the twin screens of the large-scale installation are dominated by clips from The Jazz Singer (1927), a film that predates the artist’s birth by more than 40 years. As McQueen recounts a poignant story told on his late father’s deathbed, the actor and singer Al Jolson is shown applying blackface make-up in preparation for a Broadway dress rehearsal, though the blackface itself is never actually shown – in McQueen’s version, the dark make-up causes Jolson to disappear, identifiable only by his suit and the customary white gloves of minstrelsy.

“I always wanted to work with this material,” says McQueen, shortly after unveiling Sunshine State at Rotterdam’s International Film Festival (IFFR). Specifically, the desire started 20 years ago with the idea of “erasing” Jolson from the film, introducing an element of horror that taps into a long artistic tradition – explored by the likes of Ralph Ellison and Kerry James Marshall – that equates Blackness with invisibility, and uses disappearance as a metaphor for the fragility of life as a Black man.

It’s no coincidence that the project has finally come together now, decades later. In the intervening years, The Jazz Singer – which is widely regarded as the first “talkie” – has been recognised as one of the most significant American films of all time, and officially entered the public domain at the beginning of 2023. A less obvious piece of the puzzle is the story about McQueen’s father, who was taken from the West Indies to work picking oranges in America, where he witnessed the incident of racial hatred and fatal violence that McQueen recounts in the artwork.

“[The story] is one of the last things he told me just before he died,” McQueen says, noting its anachronistic relationship to the Jazz Singer visuals, which famously follow a Jewish character “who can only be his ‘true self’ in blackface” (in other words, dressed in the identity that almost got McQueen’s father killed). Placed side by side, the two narratives could be interpreted as the parallel struggles of two men who seek to escape the bounds of their racial identity. Alternatively, they trace how the stereotypes that underpinned minstrelsy continue to have a very real impact on those that can’t simply wipe off the make-up, passed down through generations via racist media and family trauma.

As an artist and filmmaker, McQueen has followed a remarkable trajectory, from winning the Turner Prize in 1999 – for poetic, conceptual video works such as Deadpan and Drumroll – to critical and commercial acclaim for feature films such as Widows and 12 Years a Slave, which in 2013 made him the first Black British director to receive a best picture Oscar. For many artists, this kind of attention from Hollywood might have represented an opportunity for wealth, stability, and even fame, but not for McQueen, who continues to circle back to more experimental formats, including the 2020 anthology series Small Axe, a music video for Kanye West’s “All Day”, and installations like Sunshine State.

Originally commissioned to celebrate the 50th edition of IFFR in 2021 – before it was moved online for two years due to coronavirus lockdowns – Sunshine State premiered in Milan in 2022. It was McQueen’s first major commission in three years, following Year 3 at Tate Britain in 2019, and a career-spanning retrospective at Tate Modern in 2020. Now, the artwork is back in Rotterdam as originally intended, occupying a vast exhibition space at Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen in time for the 2023 edition of the film festival.

Sunshine State’s placement at the film festival is interesting because, like much of McQueen’s work, the visuals – which splice and distort the Jazz Singer rehearsal scene to disorientating effect – blur the boundary between cinema and art, a distinction that McQueen isn’t particularly interested in to begin with. “I think we’re over that now,” he says. “It’s about what the work is, and what it can be within the space.” Rotterdam is a significant stage in itself, due to its controversial history of blackface, with the Dutch tradition of Black Pete sparking a nationwide debate in recent years, amid broader discussions about racist cultural traditions.

Inevitably, these political conversations intrude on McQueen’s narrative in Sunshine State, and on his own life as a Black British artist. He tells us, for example, that he had to petition his daughter’s school in the Netherlands to give up its blackface traditions, and laments the continued relevance, in 2023, of his father’s story about the fragility of Black life. “It’s a personal story, but at the same time it’s not,” he says. “It’s a very classic story, unfortunately.”

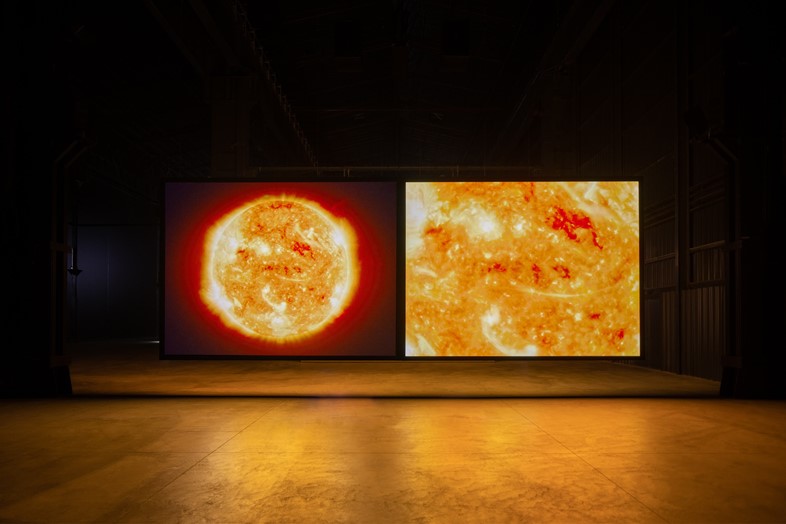

Nevertheless, the experience of watching Sunshine State is, at times, intensely intimate. When McQueen whispers the titular phrase over a smouldering image of the sun – the film’s only colour image and, as McQueen notes, the source of colour on Earth and in our skin – it takes the form of an emotional incantation. As he repeats the story his father told him, and it becomes increasingly fragmented over the course of four tellings, we get to feel the weight that it exerted on his father, and on his life, as a Black man and as a son.

“What did I discover?” he asks himself, looking back on the years-long process of creating Sunshine State. “I suppose, I was carrying shit with me... heavy shit, and I didn’t know I was carrying it. I think that weight is what I discovered, of what you carry with you. And I don’t know if I’m any lighter, but I’m more... appreciative. I’m still working it out.”

Steve McQueen’s Sunshine State will be on show at Depot Boijmans Van Beuningen until February 12.