The photographer’s stark and tender observations of British working-class life are being celebrated with a comprehensive retrospective at The Photographer’s Gallery

Chris Killip’s photographs are some of the most arresting documentations of the UK’s economic shifts during the 1970s and 80s. Spending 15 years embedded within the communities of the north-east of England, Killip’s photography transcends reportage – and a new exhibition, Chris Killip, retrospective (currently on show at The Photographers’ Gallery in London), calls attention to the immense empathy of his practice. Speaking to Dazed, the exhibition’s curator Ken Grant reflects on Killip’s long-term engagement with his subjects, stating that it “remains singular in both its immersion and its appreciation of those he photographed”.

Born in 1946 on the Isle of Man, Killip left school at 16 and, after being struck by a Henri Cartier-Bresson photo that he saw, set out on a career in commercial photography. He moved to London and then to New York, where a 1969 visit to MoMA prompted a realisation that he could make photographs “for their own sake”. In the wake of this new understanding, he returned to his birthplace, where he started capturing its fading culture by the day and working in his father’s pub by night. The exhibition opens with this series, which was made between 1970 and 1973, and consists of bucolic landscapes interspersed with rustic interiors and close-up portraits of local people.

Next, Killip began roaming north-east England where, supported by Arts Council commissions, he photographed the locals and their declining industries (1974-77). The contrast with his pastoral portraits is stark: here, small-scale subjects are overshadowed by impending backdrops of terraced houses, shipyards and coal mines.

Killip continued photographing the changing face of working-class life with his series Skinningrove, North Yorkshire (1982–84), which focuses on the friendship of a group of young fishermen – including Leso, who calmed villagers apprehensive of Killip’s presence, and Bever, whose sun-drenched squint is captured in one of the photographer’s most recognisable pictures. The unruly force of the water shaped these men’s lives and was often the bringer of untimely deaths – both Leso and his friend David drowned at sea.

In 1983, Killip moved into a caravan in Lynemouth, a beach village in Northumberland, to live with those depicted in his Seacoal series (1981-84). Despite initially being treated with suspicion, he established trust with the precarious local community who harvested waste coal from the sea. In turn, he created striking portraits, rich in form and texture, that reflect the seacoalers’ dignity and struggles. “Cookie” trudges through a snowstorm, women rummage for coal on the beach, and men drive horse-drawn carts through expansive waves. But there is joy in togetherness and play: coal pickers take refuge in caravans; young Helen plays with her hula-hoop despite the barren scene behind her. Of Lynemouth, Killip said: “The place confounded time; here the Middle Ages and the 20th century intertwined.”

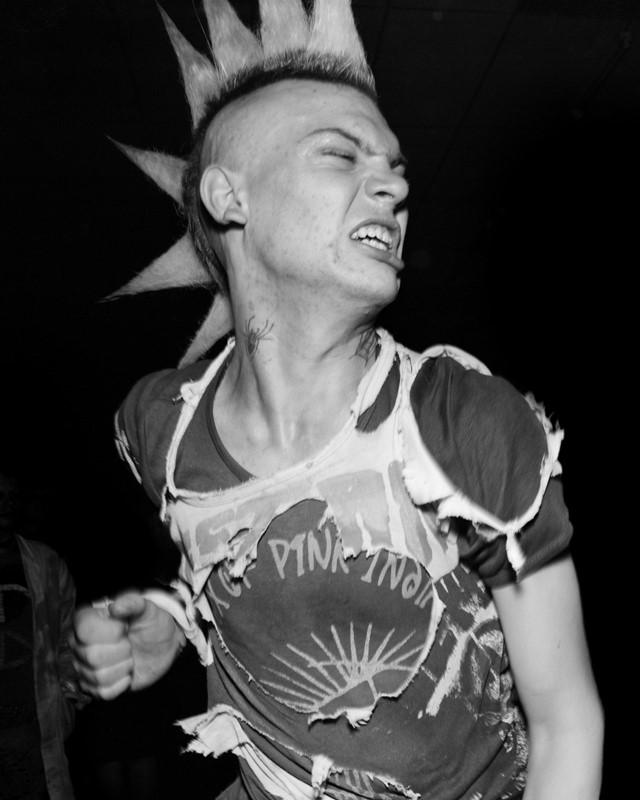

The final space of the exhibition features less familiar work – namely Killip’s documentation of the miners’ strike of 1984-85, and punk‘s renaissance in the middle of that decade. Killip’s seminal book from this era, In Flagrante (1988) includes texts by John Berger and Sylvia Grant, but Killip opened the book with Yeats’ He wishes for the Cloths of Heaven. Grant describes the poem as “cautionary, tender and humane” and, when set alongside Killip’s photographs, “quietly heartbreaking”.

His images are still as resonant as ever, considering how neglected the UK’s working-class communities are today: Grant contends the Manx photographer’s work resonates “with the austerity and breakdown that prevail in Britain.” But hope remains. Killip’s “deeply felt, humane work and the tenderness that runs through it” can “tune us into what matters – compassion, hope, togetherness – those things we can so easily lose as we navigate the times we are facing now”.

“[His work is a] landmark in the kind of committed practice that gets into the heart and under the skin of a region, showing us what needs to be valued,” adds Grant. Equally, as Lynsey Hanley notes in the exhibition catalogue, the strength of Killip’s legacy lies in his commitment to bearing witness – he “cared enough to notice”. Killip gives agency to the working-class communities who, in his words, had history “done to them”, but who, like him, refused to surrender or look away.

Chris Killip, retrospective is running at The Photographers’ Gallery until Sun 19 Feb 2023

Join Dazed Club and be part of our world! You get exclusive access to events, parties, festivals and our editors, as well as a free subscription to Dazed for a year. Join for £5/month today